As I’ve already mentioned, historical evidence about Corinth between the Persia and Peloponnesian Wars is fragmentary. One thing that does get mentioned is the city’s reputation for strife between rival political factions. Okay, that’s promising. Writing a murder mystery does require a certain amount of violence after all. Better yet, a crime novel set in the ancient world spares the author the complications of ballistics and calibres and other technical firearms stuff. As far as life in a classical Greek city goes, things become even simpler. No one’s going to cart a hoplite shield and spear around and expect to get away with a stealthy killing. This strife on the streets is going to be feet, fists and knives.

The novelist still needs to be able to write about this convincingly. How does an author do that research? Speaking for myself, I’ve studied a martial art, aikido, since 1983, and that’s proved extremely useful. No, you won’t read about Philocles or anyone else managing a faultless koshi nage or some other wholly inappropriate Japanese move. But for us to learn self-defensive techniques, and now that I am a third dan blackbelt for me to teach these things, we also learn about effective kicking and punching in our classes, to give students a realistic idea of what they might face. So that’s the first thing I have to draw on.

Secondly, occasionally, we get our movement or timing wrong. Accidents are thankfully rare, and injuries on the mat rarer still, but in the past thirty years, I have taken a couple of smacks in the face and other rather harder thumps than I was expecting. There is nothing quite like direct experience to enable a writer to realistically convey how that feels. Believe me, you don’t forget it, because you really don’t want it to happen again.

Aikido is a martial art that doesn’t meet aggression with aggression, but uses movement and an understanding of body mechanics to enable a student to avoid getting hit, and then to control an attacker with a variety of holds, pins or throws. These techniques for rendering an attacker incapable without injuring them are a major reason why over the years we have trained any number of police officers, fire fighters, nurses, paramedics, social workers and door staff. While we help them learn to stay safe, they share stories about situations they have encountered at work. Like the police inspector whose aikido skills saved his neck (not the word he used) when a violent drug dealer turned out to be immune to capsaicin, the active ingredient in the DI’s officially-issued pepper spray. So the third resource I have to draw on is that wealth of real-life experience of often inventive thuggery gleaned second-hand over post-training pints.

Lastly, those of us who study different martial arts always swap notes with each other, given half a chance. We invariably find common principles underlying our different approaches to what are the same essential challenges. I don’t only talk to blackbelts in other Japanese, Chinese and similar martial arts. Recent years have seen a great expansion of understanding and practise in HEMA – Historic European Martial Arts. I’ve had some fascinating compare-and-contrast conversations with experienced practitioners, as well as seeing some excellent displays at Living History days and in places like the Royal Amouries Museums in Leeds. All this enables me to make a fair assessment of the core skills that someone like Philocles would surely have had.

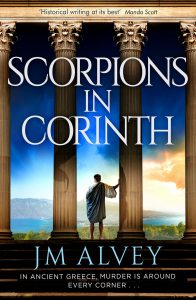

So what about a knife fight? We do also train against attacks with knives, swords and staffs in aikido. On the mat these weapons are wooden, but believe me, you still don’t want to make a mistake. We don’t only teach students how to avoid injury, but how to disarm an attacker safely as well. That’s far easier to demonstrate than it is to explain here writing, so if our paths should cross in real life, feel free to ask me about that. Meantime, you can rest assured that I know what I’m talking about when Philocles gets himself out of danger with a deft move – and I did check with an orthopaedic surgeon about the likely outcome for the person who tries to stab our hero. The stakes get increasingly high in Scorpions in Corinth.