Writing a historical mystery set in Athens takes a lot of research. There’s a great deal of material available. We have a wealth of primary sources in pots, manuscripts, statues and inscriptions. Then there are the decades of scholarly thought interpreting all those things. Finding the precise detail that a writer needs, to be certain that a vital clue or a passing reference is correct can take a whole lot of work.

Taking Philocles and his play on tour gave me pretty much the exact opposite problem. Outside Athens, and beyond its interactions with other cities, much of the history of 5th Century Greece is fragmentary, literally and metaphorically. When it comes to Corinth in particular, the focus of so much of the available research is the first century AD, thanks to the apostle Paul stopping by, and writing a couple of letters. I kept coming across things I thought I might use, until I found out they were far too late historically to be relevant for my story.

Records from earlier centuries are sparse, and physical evidence is far less readily available, for all sorts of reasons. For instance, it’s said that the Corinthians posted their civic decrees engraved on gleaming plaques of a fabled alloy known as Corinthian Bronze. Very impressive – and very easily melted down in the two and a half millenia since the city’s classical heyday. All that information is lost and gone for ever. A carved stone recording some Athenian civic honour or festival victory can also be reused of course, but when that’s found as part of a later construction, the inscriptions can still be read.

This might seem like good news for the fiction writer. Doesn’t that mean you can just make things up? Yes – and no. Not unless you’re willing to risk a well-informed reader posting a link to an academic paper that you missed. If that supplies some information contradicting that vital clue, your whole plot could unravel. Take the simple fact that Athenian actors and playwrights sometimes took their plays to other cities. We know that happened from references in the primary, contemporary, written sources. So far, so good, for the premise of this second book. But who decided which plays went on tour? Who issued invitations? Who paid the bills and why?

I needed to know – or I needed to know for certain that scholars didn’t know. Believe me, it was a great day, when I finally found an authoritative paper firmly establishing there is no evidence to answer these particular questions. That meant I was finally free to weave that fact into my historically plausible scenario, along with other scraps of Corinth’s ancient reputation, mostly mentioned in passing as the Athenians recorded their dealings and battles with the city.

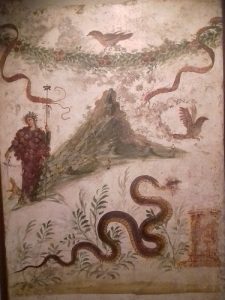

The ancients tell us Corinth was famous for its hero-worship cults. It was also known for outbreaks of civil strife. After the archaic kings were overthrown, Corinth was ruled by a Council of uncompromising oligarchs. It was a society where women lived very different lives to their Athenian sisters, even competing and winning prizes in musical competitions. The cosmopolitan population had links to the furthest Hellenic settlements to the east, and to the far distant west, thanks to Corinth’s twin ports on either side of the Isthmus. All this trade and bustle was overlooked by the brooding bulk of the Acrocorinth, the mountain fortress that ensured no army could ever leave or invade the Peloponnese without making allies of the Corinthians.

It’s all very different from home, as far as Philocles is concerned. It’s a risky place to make any misstep, even before he’s caught up in a murder…

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats.

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats. The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.