If you’re interested in the ancient world, and you can get to Oxford to visit this exhibition between now and 12th January 2020, your time will be very well spent. It’s packed with fascinating artefacts that show how the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD captured life in the cities that were overwhelmed in the midst of an ordinary day, telling us so much about how they lived, and specifically how they shopped and cooked and ate. Here’s a link to the museum’s web page for more.

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats.

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats.

I’ve seen pretty much identical things hanging in Victorian kitchens in National Trust houses.

On the other hand, another glass case held a big earthenware pot for keeping live edible dormice in, for fattening them up until you ate them. That’s not something we would ever do today! Well, not unless we’re in Croatia or Slovenia where they are still a delicacy apparently, according to curator Dr Paul Roberts, in his introductory lecture a few weeks ago. Not every country is as sentimental about fluffy animals as we are in the UK.

The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

Food was also a common motif in dining room mosaics, and the detail in this panel is incredible – the individual tesserae/tiles here are 2-3mm/an eighth of an inch square, or less. Not only that, the depictions are so accurate that the fish can be identified by species. Seriously, there’s a key on the wall beside it.

There are all sorts of other fascinating things, from the expensive dinner services used by the rich as they reclined on their triclinium couches, to the much-mended, most likely secondhand bronze pots recovered from tavern and takeaway kitchens, along with carbonised bread and fruit, and even remnants of oil and honeycomb. All evidence of everyday life so suddenly cut short.

Of course, when we think of Pompeii, one of the things most people remember are the famous plaster casts of the eruption’s victims. There’s one of a pig who never made it to a dinner table. There’s also one of a woman where resin was used rather than plaster, so the few physical remains still present are visible. I didn’t photograph that, because frankly it gave me the creeps. But it’s important to have her there, I think, to remind us of the disaster’s human cost.

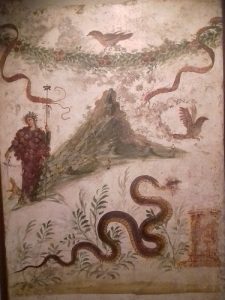

One of the most striking things for me is this picture of Bacchus/Dionysos, adorned with supersized grapes, with Mount Vesuvius as it was then, famed for its vineyards. There’s no reason to think it’s not a reasonably accurate representation. Compare this to Vesuvius today, and the scale of the eruption becomes apparent.

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats.

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats. The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.