The recent news about rabbits being a Roman import to the British Isles naturally caught my eye, though not for the reasons you might think. I was particularly interested in the range of comments between ‘but everyone already knew that’ and ‘hang on, I thought it was the Normans’. In so many cases, people were citing ‘what I learned at school…’.

I must have been on the cusp of this change in thinking, because I distinctly recall the Romans getting the credit when I was at primary school, only to be told it was the Normans when we did 1066 and all that at secondary school. In both cases, teachers I liked and respected were telling me completely different things. Hang on… So I asked my secondary school teacher to clarify who was right, who was wrong, and why. This has all stuck in my mind because it was one of those conversations that first showed me new and fascinating facets of history.

As my teacher explained, it wasn’t a case of right or wrong, but of evidence and interpretation. The Romans might well have brought rabbits over, but it was very hard to say if they became established in the wild. If they did, these small populations may well have died out well before William the Conqueror and his pals arrived. What we do have solid evidence for is the Normans establishing rabbit warrens and the little furry pests getting loose, presumably to the delight of medieval British foxes. So on balance, at the time, certainly as far as Second Form history lessons were concerned, the Normans got the credit. It’s only when you dig deeper, that you realise the foundation for that ‘fact’ isn’t as solid as it might seem.

What has this to do with writing historical fiction? Well, a writer must always bear in mind how many readers will come to a story with ‘what I learned at school’ as their yardstick for assessing how believable the historical setting might be. Depending on how long ago that was, that yardstick might be as technically outdated as feet and inches in a metric world. But a lot of people still use feet and inches. A couple of people here and there have remarked that the portrayal of the city and society in Shadows of Athens is quite markedly at odds with what they learned at school.

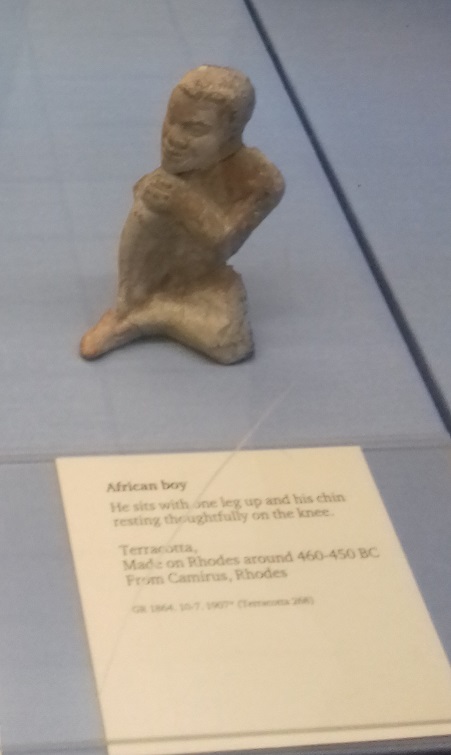

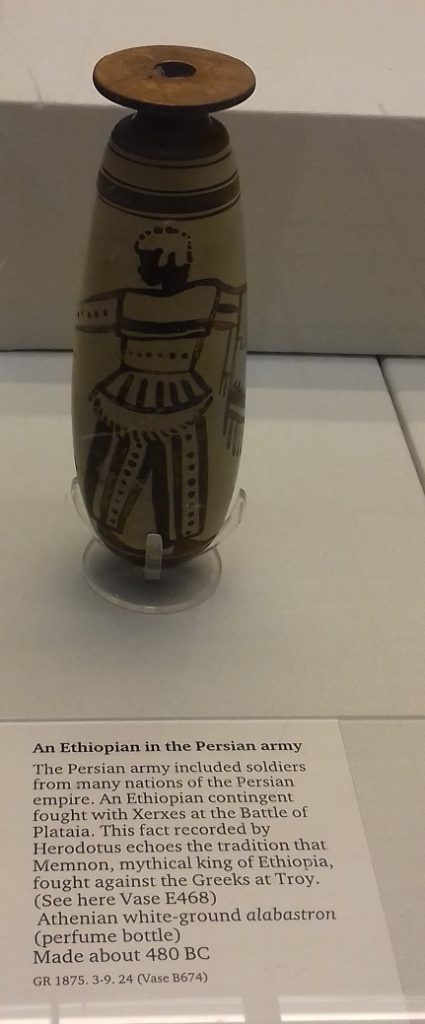

They’re not wrong – this view of 5th century BCE Greece isn’t what I learned at school either. I first had to rethink my ideas when I reached university, where I learned how much more evidence and interpretation was out there to be found. Over the past couple of years, since I first embarked on this project, I’ve had to rethink a whole load of ‘facts’ a second time. There’s a wealth of new evidence that’s been uncovered – literally – and these days historians and archaeologists work far more closely together than they did thirty years ago. In my undergraduate days, the classical texts came first and last, and anything chaps with trowels in trenches turned up was a secondary curiosity at best.

Attitudes to those classical texts has changed as well, which is to say, classical scholars are revisiting and interrogating who is telling us what and when about Ancient Athens. Let’s consider the social status of the likes of Thucydides and Xenophon, and discuss how that is likely to colour their world view. Are they really a reliable guide to working class women’s lives? Then there are academics taking a long hard look at what we’ve been told about those classical texts, when and by whom. The final two chapters of Professor Vincent Azoulay’s biography of Pericles make for fascinating reading, as he traces the evolution of the Golden Age of Pericles notion from the Enlightenment to the present day. So I need to write my books also bearing in mind those readers who will be familiar with these things that I’ve just encountered – and far, far more besides.

I need to strike a balance between these very different sorts of readers. At one end of the spectrum, there are those who learned about The Golden Age of Pericles decades ago at school, and those ‘facts’ about Classical Athens remain firmly fixed in their minds. At the other end are the readers who know far more about these things than I can ever hope to. Then there are all the many, many readers in between – as well as those who know nothing much at all about Ancient Greece and like finding out about something new.

I have two things to help me strike the right note to satisfy most of the people most of the time. Firstly, I’m writing fiction not a textbook. Historical detail in a novel underpins the sense of place and the plot. A light touch works best. I can pick and choose the evidence and interpretations that suit my purposes without dragging anyone too far out of their comfort zone – while satisfying the more knowledgable that yes, I have definitely done my reading. When it comes to the people in my story, I can rest assured that human nature then and now remains much the same. The tragedies and comedies that we have from this period show that is so time after time.

Secondly, I am the lucky beneficiary of the excellent TV documentaries we’ve seen in recent years, thanks to accomplished scholars and communicators like Mary Beard, Michael Woods, and Bettany Hughes. I’ve noticed so often how these programmes reference ‘what everybody knows’ about some aspect of the ancient world without rubbishing these ideas as outdated, but integrating those starting points with more recent discoveries and perspectives, to encourage a new outlook in their viewers.

I hope I can do something along the same lines with Philocles’ adventures, while always entertaining readers, whatever their starting point may be.

As those who’ve already read the book know, this line could have been in the book. It’s stuck in my mind because that was a point where my typing completely crashed to a halt over the question of vocabulary. It’s something that definitely challenges historical fiction authors.

As those who’ve already read the book know, this line could have been in the book. It’s stuck in my mind because that was a point where my typing completely crashed to a halt over the question of vocabulary. It’s something that definitely challenges historical fiction authors.