Anyone writing a historical novel set in ancient Greece should pour grateful libations to the memory of Pausanias, a doctor from Ionia, who was an inveterate traveller in the 2nd century AD. That is to say, he lived roughly from 110 to 180 AD. The reigns of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius were (mostly) an age of peace and prosperity for the Roman world, and Pausanias took full advantage, travelling far and wide. He wrote a detailed guide for those who might follow in his footsteps, and his Description of Greece is a fascinating read.

He wasn’t in any sense a professional historian, as we would understand it, but he diligently notes down what the locals say about the origins and founders of their cities, as well as summarising more recent events. As was always the case in the classical world, he makes no distinction between what we would call myth and history. The sons of Zeus are as real as the Roman generals who later sacked Corinth as far as Pausanias is concerned. There is similarly no question about the gods’ existence, as he details the Sanctuary of Poseidon at the Isthmus. And he really goes into all the details of the temples and the statuary, the monuments and the stadium, as well as the pine trees that adorn the site. Whenever he’s learned some interesting story about a hero or goddess, he notes that in an aside, along with observations about local customs and traditions. As he walks up the road to Corinth, he tells us about the city gates, along with the stories of the people they commemorate. Then he walks on through the marketplace, describing the many shrines and fountains. His work offers us an entertaining insight into the people of the classical world, as well as a guide to its places.

Though I would have come badly unstuck, if I had relied on Pausanias alone. He was writing hundreds of years after my story is set, and pretty much the closest he gets to dating evidence is references to before or after the days of Homer. There’s no way to tell from his text when the buildings and temples he describes were actually erected. More than once I came across a place I thought I could use, only to discover it hadn’t been there when Philocles would have needed it. For that vital information, I am indebted to ASCSA, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Founded in 1881, their affiliated scholars and students have been digging in Greece for decades, most especially in Corinth and the wider Corinthia. Their work means there’s been a wealth of papers and reports available for me online, as I researched the setting for this book. Even better, with absolutely superb timing, ASCSA recently published their fully updated site guide to Ancient Corinth. If you plan on visiting Corinth’s archaeological sites, you really should buy it. Full of detail, descriptions, maps and dates, it’s been been invaluable for my purposes. All told, ASCSA has more than earned my gratitude in this novel’s acknowledgements. (I wonder if this is the first time they’ve had a mention like this?)

Lastly, but by no means least, I’ve been able to make use of something Pausanias could never have dreamed of – Google Earth. I have been to Corinth myself and it was most definitely memorable, which is one reason I wanted to set a story here, but that was decades ago, and I had no reason to fix particular views in my mind’s eye, or in our photographs. Now, thanks to the wonders of modern technology, I could (virtually) stand on the stage of the classical Greek theatre. I can turn through a full circle and see for myself the details of the landscape that Philocles and his actors saw as the backdrop to their performance.

So the sense of place in this novel has been brought to you by resources spread over nearly two millennia!

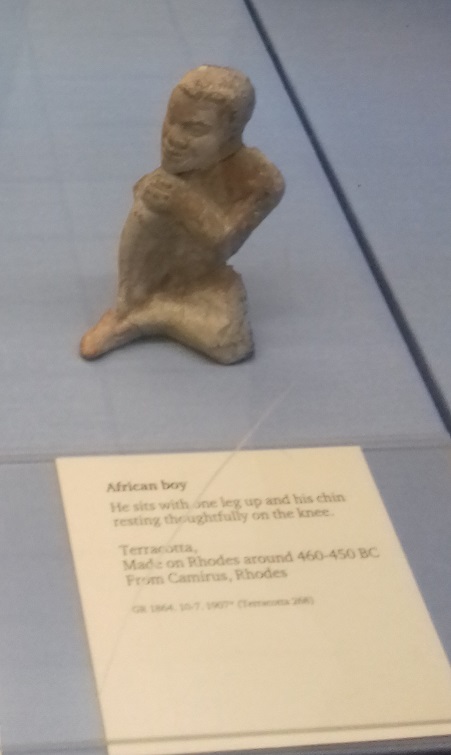

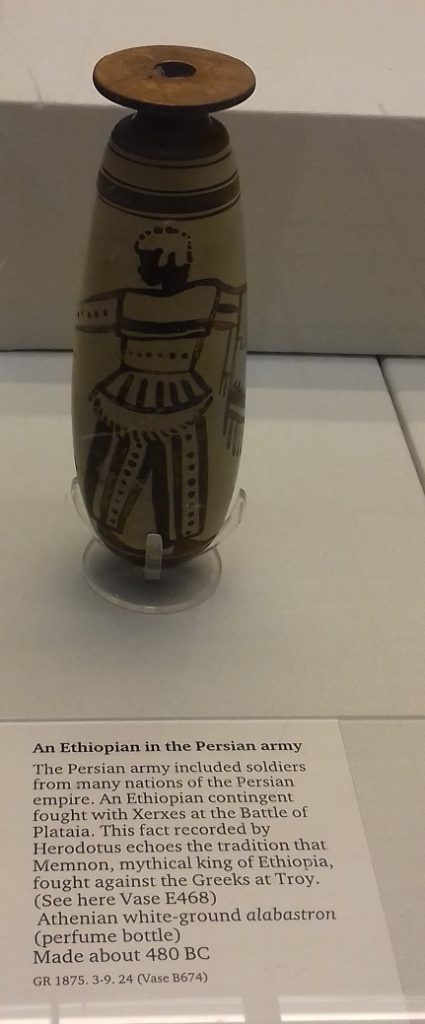

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats.

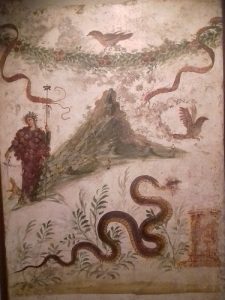

It’s one of those exhibitions where the everyday objects give us a powerful sense of connection between then and now – and the centuries in between that link us all together. Take these three mundane pieces of kitchenware – and apologies for my less than skilled photography. Here’s a frying pan, a bun tin, and a fancy mould for puddings or forcemeats. The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

The Romans certainly weren’t. This cute rabbit is eating the figs that he’s about to be cooked with… There are several pictures from frescos with a similar theme, showing this was a popular decorative idea for kitchens.

As those who’ve already read the book know, this line could have been in the book. It’s stuck in my mind because that was a point where my typing completely crashed to a halt over the question of vocabulary. It’s something that definitely challenges historical fiction authors.

As those who’ve already read the book know, this line could have been in the book. It’s stuck in my mind because that was a point where my typing completely crashed to a halt over the question of vocabulary. It’s something that definitely challenges historical fiction authors.