There’s a great deal of talk in the media at the moment about concepts like borders and nationality. History is frequently, and highly selectively, cited as evidence for whatever political point of view is being promoted. Meantime, tangible history, by way of archaeological artefacts, keeps reminding us that the world has always been interconnected, and that people have always moved around.

It’s taken two years, but experts have now identified a glass shard found at Chedworth Villa in the Cotswolds as part of a bottle from the Black Sea region, brought all the way to Roman Britain. You can read the full story here. Now, Chedworth’s inhabitants were clearly among the wealthy elite, so I don’t suppose they bought this perfume or whatever the bottle contained, from a stall in Corinium market, but the fact remains that this valuable thing passed from hand to hand over thousands of miles to end up in an ordinary, if well-resourced, household. This is of course merely the latest such discovery to indicate that the British Isles have always had ties to the European mainland, and far beyond. See also the Vindolanda letters, the Staffordshire Hoard etc. etc. etc.

Then there’s the recent find in Greece, that may be the oldest Homo Sapiens skull found outside Africa. If so, it takes the modern human dispersal into Europe back tens of thousands of years. That raises the possibility of Homo Sapiens and Neanderthal co-existing for countless generations. This catches my eye in particular because that particular narrative is one that’s changed and shifted over the past century, reflecting all sorts of often problematic things about the decade when a particular theory held sway. When I was a kid in the 70s, the story we were told was a simple one; superior Homo Sapiens drove out the inferior Neanderthals, who were always drawn as nasty, brutish and short. That theory’s since been modified, first with talk of the Neanderthals coming second in competition for resources, and more recently still, on account of their theorised inability to adapt to climate change. When it comes to whether or not Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens could interbreed, the arguments remain heated even with new genetic evidence.

How much of this is unintentional projection, based on current preoccupations? How much of this is attempting to secure history’s endorsement for what is in fact quite simply racism, when the obscuring layers of argument are peeled away? I am always very careful to pick apart the reasoning when politicians and the like start using their preferred version of history as a way of putting an end to arguments about contentious policies in the modern day.

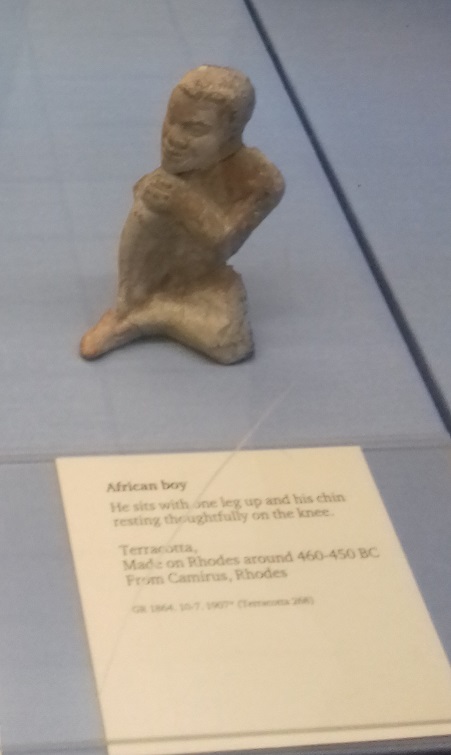

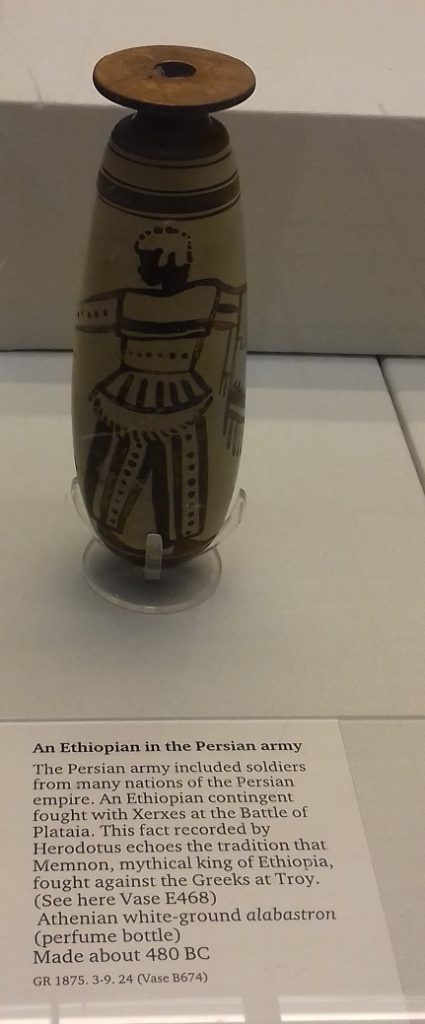

That’s why I think it’s important for historical fiction to reflect the world as accurately it was, insofar as we can possibly tell. That’s one reason why there are characters of colour in both Shadows of Athens and Scorpions in Corinth. Not because they have to be there for some plot-related reason. Simply because they would have been there. Writers from Herodotus onward make it very clear that people have always moved around. As did a couple of nice artefacts that I spotted on that recent visit to the British Museum.